Whilst collating a plethora of new artists to write about I simply must include Käthe Kollwitz – Germany’s Leonardo Da Vinci.

The expressions of emotion are rapturous.

Aptly scroll downwards to take in her bodily forms, skilful compositions and empathic range. Käthe Kollwitz (8 July 1867 – 22 April 1945) often incorporates mutual perspective with the subjects of her work. A myriad configurations given the ‘I defy you to ignore this message’ treatment.

Powerful social, spiritual and political commentaries abound throughout her work.

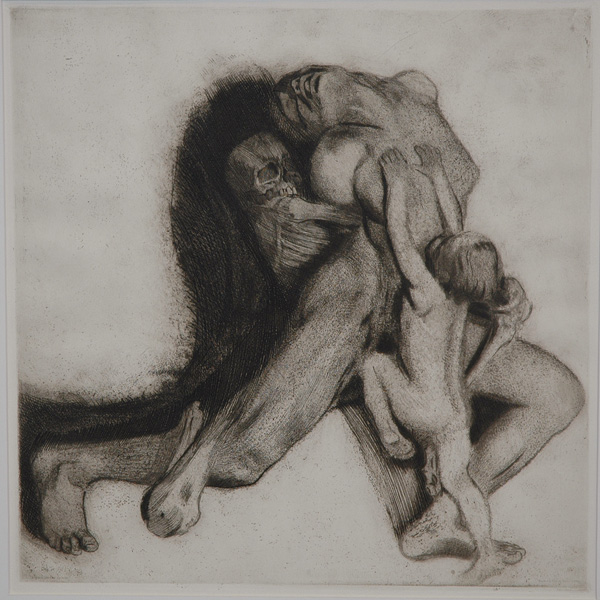

Tod und Frau / Death and Woman – Self-portrait – Original Line etching, drypoint, sandpaper, soft ground with imprint of granulated tone paper and Ziegler’s transfer paper and roulette [1910].

Two revealing quotes by Kollwitz allude to an ambition and sensitivity often found in great artists:

‘How long were the stretches of toilsome tacking back and forth, of being blocked, of being thrown back again and again. But all that was annulled by the periods when I had my technique in hand and succeeded in doing what I wanted.’

‘While I drew, and wept along with the terrified children I was drawing, I really felt the burden I am bearing. I felt that I have no right to withdraw from the responsibility of being an advocate. It is my duty to voice the suffering of men, the never-ending sufferings heaped mountain-high.’

The first quotation includes technical art language. Stretching the art canvas across wooden beams describes the labour of work before the work of painting has actually begun. Also, the ‘blocked’ method of using masking materials such as tape to paint a specified area in contrast to another. Kollwitz even seems to explain a measure of rejection for her work prior to success.

Kollwitz exclaims her social responsibilities through her art. Tearful heart-wrenching involvement in bringing forth the cold reality of deplorable living conditions that she witnessed. Interestingly this particular commentary makes mention of children and men.

True to Kollwitz’ dramatically tragic style I decided to add a different kind of beauty in ‘Woman With Orange’, 1901:

!['Woman with Orange' [1901] by Käthe Kollwitz - colour etching, aquatint and lithograph on paper - mounted on grey-violet card - 16 cm x 27.9 cm.](https://theunfathomableartist.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/kollwitz-woman-with-orange.jpg?w=278&h=563)

‘Woman with Orange’ [1901] by Käthe Kollwitz – colour etching, aquatint and lithograph on paper – mounted on grey-violet card – 16 cm x 27.9 cm.

Of course the gravitas of her work remains solemn and forceful.

Kollwitz has such a tremendous body of work – Monet-like for its vast quality. Furthermore, there is a wealth of styles, techniques and methods to be found throughout her life in art. Sculptures, woodcuts, lithography, sketches, posters, charcoals, paints et al.

By the 1890’s Kollwitz most often switches to etching rather than the use of oils. Her etches frequently stylistic in representation to accommodate the growing popularity of the printing press and its mass artistic appeal. The melancholic, serious nature of her work best serviced through monochromatic depictions along with the ability to positively influence the public psyche.

Clearly Kollwitz becomes Germany’s Da Vinci by the depth of her exemplary artistic Expressionism.

![Anguish: The Widow [1916] by Käthe Kollwitz.](https://theunfathomableartist.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/kollwitz.gif?w=696)